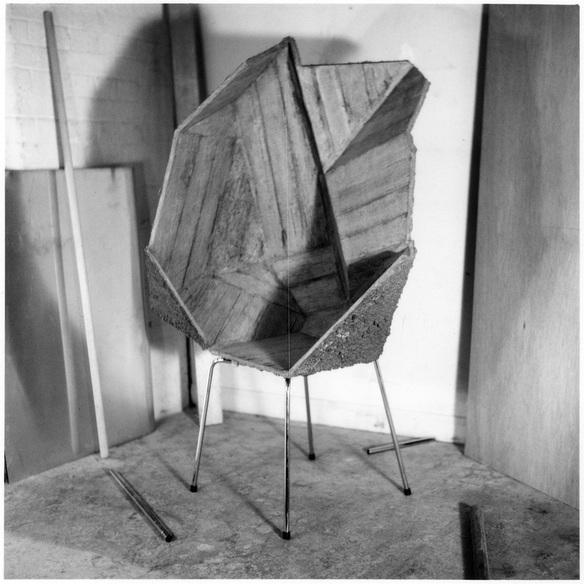

Inside this tattered shoebox lies a single square photograph, a black and white image from a different time and place. You pick it up and understand instinctively you are looking at your future self.

You work for an international cartel of furniture distributors, specialising in the grey market of quality reproductions of 20th Century modernist chairs. Mostly, you source potential new manufacturers and maintain quality control across your allocated Far East sector. The job matches the surroundings you live in, a recent New Town development emulating the architectural vernacular of one of your main client countries in the West, a quality reproduction like the chairs you deal in – the Wassily, the Hardoy, the Tulip, the Ax, the Barcelona, La Fonda, the Swan, the Series 7.

You have never travelled outside of your own country, so you cannot be certain, but you suspect it may be a rather idealised past, or future, that is set here in brightly painted concrete. The place is still being built, following an intricate pattern of development in which completed phases are interspersed by incomplete tracts, giving the impression of a place eternally rehearsing its entire life cycle in an instant. Even though most real estate, actual and projected, has been snapped up, it has been purely for investment reasons, and so the homes remain mostly lacking of actual tenants. The dominant demographic of this town consists of an army of cleaners who comb the deserted streets and pedestrian zones, row along the gentle canals and preen the car ports, keeping at bay the eternal dust and dirt generated by the interspersed construction zones. The handful of actual, living residents like yourself are scattered across the town; like the dust that hangs in the air, you feel their presence though you never see them.

The economic slow down in your client countries has given you unprecedented spare time, and you have learnt to fill this void with long walks amongst the new and unfinished buildings of your neighbourhood. Having eventually grown tired of the constant noise of the surrounding construction, you have lately taken to explore the quiet, infinite depths of the empty shopping mall which lies at the lifeless heart of this new town. Like the town that was supposed to supply it with custom, it grew too fast to fill the void inside. The shopping mall is simply called Centre Centre, the doubling of its social and geographic positioning no doubt intended to exponentially boost its economic gravity. Its present condition of underwhelming occupancy would imply the one Centre cancelling out the other, creating a mystical zero, a vacuum, a time capsule floating in deep space.

The food court in this vast complex, originally your first destination as it is the heart and stomach of any mall, is a sea of multi-coloured plastic eating units, each one consisting of a round table with five chairs encircling it, all connected by a single undulating chrome steel tube. You suppose they were intended to look like flowers, and every time you come here you think of a sea of petals, Mao's hundred flowers forever blooming under a fluorescent sky. It is a bastardised design, though not without its charm, certainly not like any of the adaptations you have seen in your own factories. Out of curiosity you once looked into where these were produced, self-consciously kneeling on the floor to look for that elusive manufacturer's mark on the underside, but you could find none. This in itself was a clue to their imported nature, probably from one of the south-eastern economies which are beginning to enter your market, and you learned to appreciate the smell of foreign injection-moulded plastic and the premature patina resulting from the inferior pigments used in their manufacture.

Of the dozen or so food outlets, only two are occupied and running. Despite the terminal underpopulation of the town, the two outlets run a full service. This is not surprising since they belong to state-owned fast food chains which are subsidised and therefore not subject to the vagaries of demand and supply. You only eat from one of them, an outlet from the Freedom Fresh chain which specialises in salads, juices and smoothies which are freshly prepared in front of you. The young man who works behind the counter reminds you of your younger self, around the age when you first started working in this business of furniture. Back then it was your uncle who took you under his wings and got you your first job in his factory specialising in tubular steel furniture and fittings. You had received your education in 20th Century furniture design from the black-and-white photocopies pinned up all across your uncle's office, a scattered and circular history of rectal support organised according to prevailing market tastes and reproducability in the then limited, but nevertheless ambitious capacity of your uncle's factory. Many of the images were severly degraded photocopies of photocopies of photocopies, and you distinctly remember your amazement at how some of these vague images in which you sometimes barely recognised an object, nevermind a piece of furniture, demanded a considerable amount of imagination to fill in the missing information and produce a chair out of. There was a story which the workers at the factory liked to rehearse in various versions, a story about a new worker who was given the task of reproducing a prototype copy from one of these images and who eventually fell into despair when he produced an unwieldy object which, as it later turned out, was the chair and its shadow combined in a single object.

At Freedom Fresh you generally order the same salad, "Number 12: Autumn Reds," composed mostly of shredded beetroot. Occasionally, you order a different dish, a random selection from their menu such as "Number 4: Lucky Spring" or "Number 18: Prosperous Green," to avoid the situation where the young man might start to prepare "Number 12: Autumn Reds" before you arrive and thus deny you the small spectacle which is the very reason for your repeat custom. You watch him first peel the skin of the beets, then rasp them by hand. He has all sorts of electrical food processors at his disposal, but for some reason he chooses to rasp the beetroot by hand. Which is why you watch him every week and he obviously enjoys the audience. There is a point soon after he begins when the deep red juice of the beetroot is splattering everywhere, bubbling and flowing from his wrists and fingers like some unnamable massacre. The sweet, earthen smell that fills the air between you makes up for the lack of verbal comunication. He lives in the neighbouring village, but that is as much as you need to know about him.

Over time you come to realise the reason for this increasingly committed viewing every week: it is the one moment in which you are able to embrace the constant dull pain emanating from your left leg, or where you think it is, and your mind loosens its embargo on the memory of the accident. It occured on one of your factory visits, a potential new supplier near the northern border. It was a vast compound specialising in all variants of thermoplastics, a company which had originally cornered the niche market of medical prosthetics and had then decided to expand into furniture production. You were being shown their recent acquisition of second-hand injection-moulding machines, each roughly the size of a bus, while workers were being trained on them, possibly in anticipation of your forthcoming contract. You had not been yourself that day, having forgotten the obligatory bottle of whiskey as a gift to your host, and your anxiety from this unforgivable oversight only heightened your increasing confusion caused by the already overbearing fumes throughout the factory. In a sequence of events which you later read in the incident report (since your own memory has rejected it much like a foreign body) you must have stepped backwards into an open mould of a large-scale prototyping machine just as it was closing to vacuum-form the heated polypropylene plastic. You have every reason to suspect that the prosthetic splint which now takes the place of your limb was most likely manufactured in the very same factory. Somewhere on the inside of this splint is the manufacturer's seal which you have never seen but feel like an incurable itch.

Your ritual lunch is always followed by a long, meandering walk through the inner bowels of the mall. It helps to balance out the delicate moment of selective recollection while watching your meal being prepared, an experience you recoil from in quiet distress and yet continue to return to like a moth to its light. The walks allow you to empty your mind, to reset the inner coil. This is what the mall provides you with, the luxury of exercising your forgetting – your goldfish treadmill, as you like to think of it. The vast complex seems to be laid out on a perfectly symmetrical plan, so much so that wherever you happen to be in it, it never fails to unfold symmetrically in front of you. Occasional encounters with those illuminated panels displaying the floor plan leave you none the wiser as they have not been customised to include the little red dot indicating your present location. Most appear to be alternately caked in by a layer of greasy dust or remain wrapped by the fabricators to avoid just such fate, both producing an altogether not unpleasant effect of ancient hieroglyphs speaking to you across distant time. What you are left with is the repeated image of an insect wholly encompassed by the acephalic network of its spidery limbs.

On this particular day, you find yourself at an interjunction of passageways which you believe you have not traversed yet, though you cannot be sure. You got distracted earlier while walking down another set of junctions, absentmindedly wiping your mouth and looking with resigned suprise at the remnants of your beetroot lunch across the right sleeve of your shirt. Although you go to great lengths to pretend otherwise, you devise ever more self-deceiving tactics to miss a turn or two, since you relish this moment of being lost perpetuating the impression of the infinite configuration of walks open to you. Earlier today, you had half-consciously neglected to wipe your mouth after lunch so as to create an opportunity, an opening, to distract yourself at a later point.

And once again, you have schemed yourself into getting lost. A peculiar smell hangs in the air and draws you down a set of corridors; it is a heavy note of fermentation, not without a hint of untreated sewage and possibly a dead rodent or two, but unusually, with a distinctly inorganic, mineral edge to it. A pungent smell, both wet and dry, that is appalling, and yet irresistably drawing you into its orbit, providing you with a certain criteria, an alibi, to walk down one amongst many seemingly identical corridors. Over time, of course, you have learnt to savour the subtle nuances of these countless arteries like the whiskey you forgot on that cruel day. The bouquet of stale air, varying in its composition of dust, humidity, grease, interacting with the occasional flourish of brightly coloured discarded plastic, variations in lighting and the ripe, lingering body of organic waste providing the finishing note. The corridor you find yourself in today shares many of these qualities, qualities which provide you with the perfect recepticle for your empty thoughts: row upon row of vacant retail spaces, bare concrete hulls with their utility services exposed, like some hollowed carcass of a dead beetle on the insatiable forest floor.

The passage in front of you seems unusually dark, with some of the light fixtures already hanging precariously from the suspended ceiling which is itself in advanced stages of disintegration. This particular tableau reminds you of a programme you recently watched on television, featuring an ancient gallion at the bottom of the sea, the robotic camera aboard the mini-submarine tracking slow sequences along the abandoned berths of a once proud vessel. There is no algae growing in these corners, however, just occasional small piles of rubbish, little altars of polystyrene bowls and bamboo chopsticks whose hot contents once sated the urgent hunger of a construction worker or security guard. Never a cleaner, though; not because the cleaners are conscientious about their rubbish, but because no cleaner ventures this far into the maze, not since the grand opening two years ago. Unlike those small organic shapes which normally break the geometric lines enveloping you, you find yourself increasingly surrounded by orderly piles of timber, breeze blocks, lighting fixtures and floor tiles. It remains unclear to you whether these have yet to be installed or are in the process of being reclaimed. As you move on, increasingly large patches of untiled floor, exposing the bare concrete skin underneath, are producing an anxious sense in you of approaching one of those dead ends which you had always assumed to exist but have never so far actually come across. You are now walking through a barely lit tunnel of rough, unfinished concrete, the sharp surface exposing the texture of its formwork. The option of turning around was left several junctions back, there is now only a single objective: to touch the wall that ends the tunnel.

You almost walk into it thinking it is yet another intermittent spell of darkness. You turn around, realising the corridor is barely wide enough to fit your shoulders, and you notice a rectangular shape by your left foot: a shoebox. It seems utterly out of place, here in your cavity, with a patina, an age that is different to the accelerated ruin around you. A brand you do not recognise, a distinctly old-fashioned swirl to the font, a quality cardboard visibly made from real wood pulp, a pulp that speaks of the forest it once came from. It is just a shoebox, and yet you cannot help yourself and proceed to open it.

Bernd Behr, Phantom Limbs, 2011, B&W photograph and text.

Schmidt, S. (2014) 'Odradek oder die Rache des Objektes? "Phantom Limbs" von Bernd Behr', in Schmidt, S. (ed.) Sprachen des Sammelns. Literatur als Medium und Reflexionsform des Sammelns. Paderborn: Wilhelm Fink, pp. 131-138.

You work for an international cartel of furniture distributors, specialising in the grey market of quality reproductions of 20th Century modernist chairs. Mostly, you source potential new manufacturers and maintain quality control across your allocated Far East sector. The job matches the surroundings you live in, a recent New Town development emulating the architectural vernacular of one of your main client countries in the West, a quality reproduction like the chairs you deal in – the Wassily, the Hardoy, the Tulip, the Ax, the Barcelona, La Fonda, the Swan, the Series 7.

You have never travelled outside of your own country, so you cannot be certain, but you suspect it may be a rather idealised past, or future, that is set here in brightly painted concrete. The place is still being built, following an intricate pattern of development in which completed phases are interspersed by incomplete tracts, giving the impression of a place eternally rehearsing its entire life cycle in an instant. Even though most real estate, actual and projected, has been snapped up, it has been purely for investment reasons, and so the homes remain mostly lacking of actual tenants. The dominant demographic of this town consists of an army of cleaners who comb the deserted streets and pedestrian zones, row along the gentle canals and preen the car ports, keeping at bay the eternal dust and dirt generated by the interspersed construction zones. The handful of actual, living residents like yourself are scattered across the town; like the dust that hangs in the air, you feel their presence though you never see them.

The economic slow down in your client countries has given you unprecedented spare time, and you have learnt to fill this void with long walks amongst the new and unfinished buildings of your neighbourhood. Having eventually grown tired of the constant noise of the surrounding construction, you have lately taken to explore the quiet, infinite depths of the empty shopping mall which lies at the lifeless heart of this new town. Like the town that was supposed to supply it with custom, it grew too fast to fill the void inside. The shopping mall is simply called Centre Centre, the doubling of its social and geographic positioning no doubt intended to exponentially boost its economic gravity. Its present condition of underwhelming occupancy would imply the one Centre cancelling out the other, creating a mystical zero, a vacuum, a time capsule floating in deep space.

The food court in this vast complex, originally your first destination as it is the heart and stomach of any mall, is a sea of multi-coloured plastic eating units, each one consisting of a round table with five chairs encircling it, all connected by a single undulating chrome steel tube. You suppose they were intended to look like flowers, and every time you come here you think of a sea of petals, Mao's hundred flowers forever blooming under a fluorescent sky. It is a bastardised design, though not without its charm, certainly not like any of the adaptations you have seen in your own factories. Out of curiosity you once looked into where these were produced, self-consciously kneeling on the floor to look for that elusive manufacturer's mark on the underside, but you could find none. This in itself was a clue to their imported nature, probably from one of the south-eastern economies which are beginning to enter your market, and you learned to appreciate the smell of foreign injection-moulded plastic and the premature patina resulting from the inferior pigments used in their manufacture.

Of the dozen or so food outlets, only two are occupied and running. Despite the terminal underpopulation of the town, the two outlets run a full service. This is not surprising since they belong to state-owned fast food chains which are subsidised and therefore not subject to the vagaries of demand and supply. You only eat from one of them, an outlet from the Freedom Fresh chain which specialises in salads, juices and smoothies which are freshly prepared in front of you. The young man who works behind the counter reminds you of your younger self, around the age when you first started working in this business of furniture. Back then it was your uncle who took you under his wings and got you your first job in his factory specialising in tubular steel furniture and fittings. You had received your education in 20th Century furniture design from the black-and-white photocopies pinned up all across your uncle's office, a scattered and circular history of rectal support organised according to prevailing market tastes and reproducability in the then limited, but nevertheless ambitious capacity of your uncle's factory. Many of the images were severly degraded photocopies of photocopies of photocopies, and you distinctly remember your amazement at how some of these vague images in which you sometimes barely recognised an object, nevermind a piece of furniture, demanded a considerable amount of imagination to fill in the missing information and produce a chair out of. There was a story which the workers at the factory liked to rehearse in various versions, a story about a new worker who was given the task of reproducing a prototype copy from one of these images and who eventually fell into despair when he produced an unwieldy object which, as it later turned out, was the chair and its shadow combined in a single object.

At Freedom Fresh you generally order the same salad, "Number 12: Autumn Reds," composed mostly of shredded beetroot. Occasionally, you order a different dish, a random selection from their menu such as "Number 4: Lucky Spring" or "Number 18: Prosperous Green," to avoid the situation where the young man might start to prepare "Number 12: Autumn Reds" before you arrive and thus deny you the small spectacle which is the very reason for your repeat custom. You watch him first peel the skin of the beets, then rasp them by hand. He has all sorts of electrical food processors at his disposal, but for some reason he chooses to rasp the beetroot by hand. Which is why you watch him every week and he obviously enjoys the audience. There is a point soon after he begins when the deep red juice of the beetroot is splattering everywhere, bubbling and flowing from his wrists and fingers like some unnamable massacre. The sweet, earthen smell that fills the air between you makes up for the lack of verbal comunication. He lives in the neighbouring village, but that is as much as you need to know about him.

Over time you come to realise the reason for this increasingly committed viewing every week: it is the one moment in which you are able to embrace the constant dull pain emanating from your left leg, or where you think it is, and your mind loosens its embargo on the memory of the accident. It occured on one of your factory visits, a potential new supplier near the northern border. It was a vast compound specialising in all variants of thermoplastics, a company which had originally cornered the niche market of medical prosthetics and had then decided to expand into furniture production. You were being shown their recent acquisition of second-hand injection-moulding machines, each roughly the size of a bus, while workers were being trained on them, possibly in anticipation of your forthcoming contract. You had not been yourself that day, having forgotten the obligatory bottle of whiskey as a gift to your host, and your anxiety from this unforgivable oversight only heightened your increasing confusion caused by the already overbearing fumes throughout the factory. In a sequence of events which you later read in the incident report (since your own memory has rejected it much like a foreign body) you must have stepped backwards into an open mould of a large-scale prototyping machine just as it was closing to vacuum-form the heated polypropylene plastic. You have every reason to suspect that the prosthetic splint which now takes the place of your limb was most likely manufactured in the very same factory. Somewhere on the inside of this splint is the manufacturer's seal which you have never seen but feel like an incurable itch.

Your ritual lunch is always followed by a long, meandering walk through the inner bowels of the mall. It helps to balance out the delicate moment of selective recollection while watching your meal being prepared, an experience you recoil from in quiet distress and yet continue to return to like a moth to its light. The walks allow you to empty your mind, to reset the inner coil. This is what the mall provides you with, the luxury of exercising your forgetting – your goldfish treadmill, as you like to think of it. The vast complex seems to be laid out on a perfectly symmetrical plan, so much so that wherever you happen to be in it, it never fails to unfold symmetrically in front of you. Occasional encounters with those illuminated panels displaying the floor plan leave you none the wiser as they have not been customised to include the little red dot indicating your present location. Most appear to be alternately caked in by a layer of greasy dust or remain wrapped by the fabricators to avoid just such fate, both producing an altogether not unpleasant effect of ancient hieroglyphs speaking to you across distant time. What you are left with is the repeated image of an insect wholly encompassed by the acephalic network of its spidery limbs.

On this particular day, you find yourself at an interjunction of passageways which you believe you have not traversed yet, though you cannot be sure. You got distracted earlier while walking down another set of junctions, absentmindedly wiping your mouth and looking with resigned suprise at the remnants of your beetroot lunch across the right sleeve of your shirt. Although you go to great lengths to pretend otherwise, you devise ever more self-deceiving tactics to miss a turn or two, since you relish this moment of being lost perpetuating the impression of the infinite configuration of walks open to you. Earlier today, you had half-consciously neglected to wipe your mouth after lunch so as to create an opportunity, an opening, to distract yourself at a later point.

And once again, you have schemed yourself into getting lost. A peculiar smell hangs in the air and draws you down a set of corridors; it is a heavy note of fermentation, not without a hint of untreated sewage and possibly a dead rodent or two, but unusually, with a distinctly inorganic, mineral edge to it. A pungent smell, both wet and dry, that is appalling, and yet irresistably drawing you into its orbit, providing you with a certain criteria, an alibi, to walk down one amongst many seemingly identical corridors. Over time, of course, you have learnt to savour the subtle nuances of these countless arteries like the whiskey you forgot on that cruel day. The bouquet of stale air, varying in its composition of dust, humidity, grease, interacting with the occasional flourish of brightly coloured discarded plastic, variations in lighting and the ripe, lingering body of organic waste providing the finishing note. The corridor you find yourself in today shares many of these qualities, qualities which provide you with the perfect recepticle for your empty thoughts: row upon row of vacant retail spaces, bare concrete hulls with their utility services exposed, like some hollowed carcass of a dead beetle on the insatiable forest floor.

The passage in front of you seems unusually dark, with some of the light fixtures already hanging precariously from the suspended ceiling which is itself in advanced stages of disintegration. This particular tableau reminds you of a programme you recently watched on television, featuring an ancient gallion at the bottom of the sea, the robotic camera aboard the mini-submarine tracking slow sequences along the abandoned berths of a once proud vessel. There is no algae growing in these corners, however, just occasional small piles of rubbish, little altars of polystyrene bowls and bamboo chopsticks whose hot contents once sated the urgent hunger of a construction worker or security guard. Never a cleaner, though; not because the cleaners are conscientious about their rubbish, but because no cleaner ventures this far into the maze, not since the grand opening two years ago. Unlike those small organic shapes which normally break the geometric lines enveloping you, you find yourself increasingly surrounded by orderly piles of timber, breeze blocks, lighting fixtures and floor tiles. It remains unclear to you whether these have yet to be installed or are in the process of being reclaimed. As you move on, increasingly large patches of untiled floor, exposing the bare concrete skin underneath, are producing an anxious sense in you of approaching one of those dead ends which you had always assumed to exist but have never so far actually come across. You are now walking through a barely lit tunnel of rough, unfinished concrete, the sharp surface exposing the texture of its formwork. The option of turning around was left several junctions back, there is now only a single objective: to touch the wall that ends the tunnel.

You almost walk into it thinking it is yet another intermittent spell of darkness. You turn around, realising the corridor is barely wide enough to fit your shoulders, and you notice a rectangular shape by your left foot: a shoebox. It seems utterly out of place, here in your cavity, with a patina, an age that is different to the accelerated ruin around you. A brand you do not recognise, a distinctly old-fashioned swirl to the font, a quality cardboard visibly made from real wood pulp, a pulp that speaks of the forest it once came from. It is just a shoebox, and yet you cannot help yourself and proceed to open it.

Bernd Behr, Phantom Limbs, 2011, B&W photograph and text.

Schmidt, S. (2014) 'Odradek oder die Rache des Objektes? "Phantom Limbs" von Bernd Behr', in Schmidt, S. (ed.) Sprachen des Sammelns. Literatur als Medium und Reflexionsform des Sammelns. Paderborn: Wilhelm Fink, pp. 131-138.